Elegy for Mrs. Doris Anna Macdougall - Griffin - a Personal Lament

September 7, 1935 - March 23, 2024

Elegy for Mrs. Doris Anna Macdougall - Griffin - a Personal Lament

September 7, 1935 - March 23, 2024

It has been seven days since you flew.

Seven days since my daughter and I sat with you, prayed the Rosary, The Sorrowful Mysteries, over your sleeping body, the last of your clan to be with you. Seven days since we told you we loved you, and that you were Heaven bound. Seven days since you died on a Saturday, the same day you were born, the day of The Joyful Mysteries.

Seven days since I stroked your silky forehead over and over with my left hand, gently, awkwardly, telling you in whispers: “It’s okay, Mom. I’m here. Theresa is here. I’m here now. I’m here with Amelia.” Seven days since I watched your brow and face relax, seven days since I promised you I would see you again, knowing that at least in this world, I would not.

Seven days since my daughter wept over you, and prayed over you and ached over you, the last to be with you, the last to touch you, kiss you and comfort you.

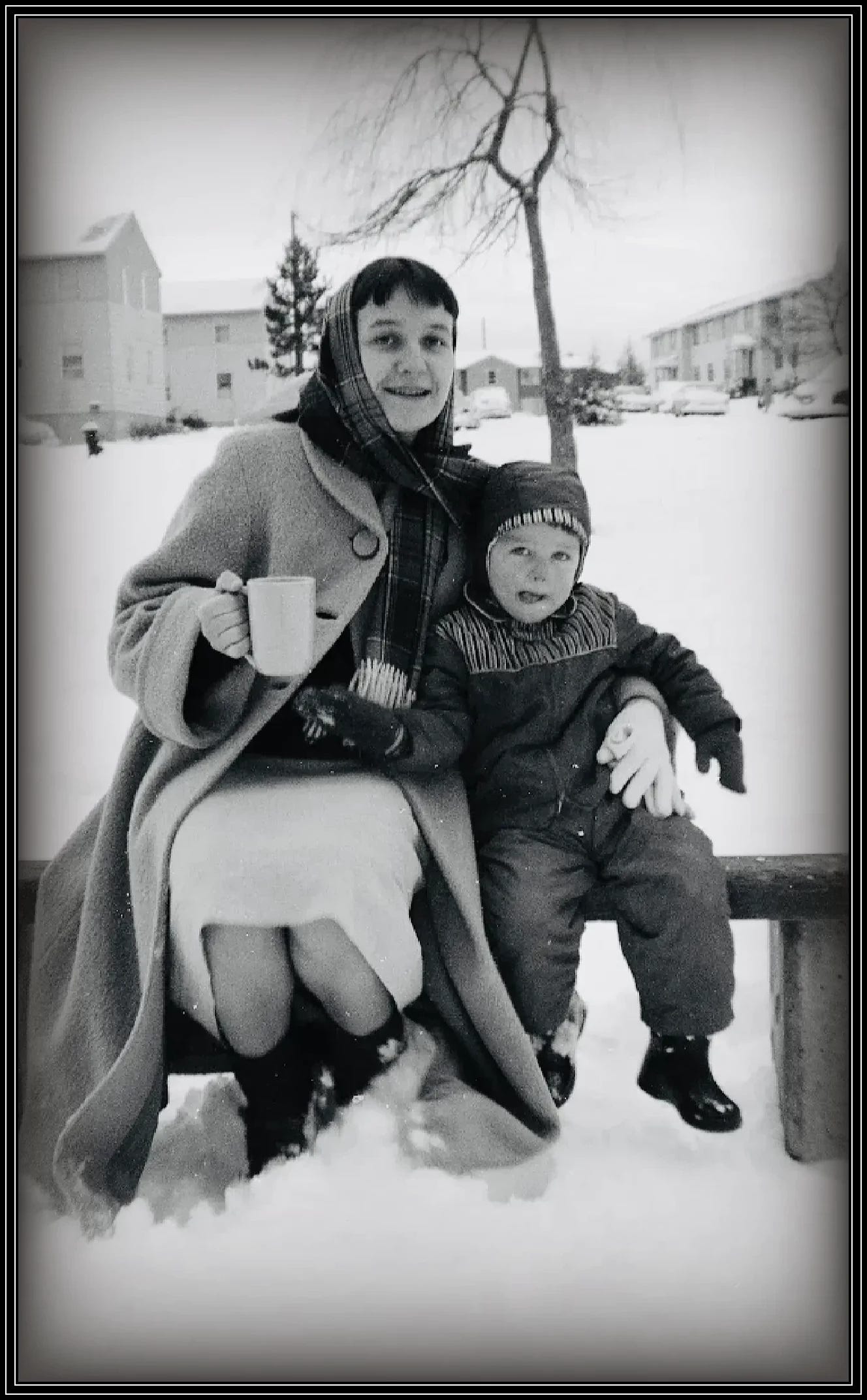

Mama, how do I tell anything of your long story of hardship and suffering? How do I begin that story? How do I end it? How you bore nine children? How your endless optimism informed my own optimism? How your bottomless sadness informed my own bottomless sadness? How religion was the only thing that sustained you, the only thread of hope you had in that lonely year, 1939, the year your grandfather told you that God would always love you and you would never be alone?

It was the year of great films, at age four, that they took you away from your mother and rescued you from the blue din of her madness. How do I tell of that Oliver Twist childhood? Is it even possible?

Probably not.

I have gathered your things, just the other day, four white bankers boxes filled with small objects of little value. Four of your fine blankets, and a few of your favorite articles of clothing. They hang in my closet now. Your favorite jackets, including the silk one that made you feel so special.

I am looking for clues, in much the same way I looked for clues when I sorted through Mary’s little trinkets, after she died. She, the third of your five daughters and the second daughter to die before you.

Pretty things that sparkled and shone. Pretty things still in their packaging, for that was how Mary kept her precious things, precious, by never unwrapping them, by keeping them pristine, and untouched.

I am sorting through your old things now, looking for clues, the way I’m always looking for clues.

Daddy said once: “You're the archivist of this family, Theresa.” It made him smile to see the things I had saved from the city dump moldering across town. Old wooden toys he had made when we were kids, all of the letters and cards he ever sent me, old photographs, odd things of little value, like the wooden display that you decorated every Christmas with the Nativity set we used to have.

These silly, sentimental things are alive with our memories, a glowing collection in dust and purple shadow.

And I have the books you loved, books on embroidery and needlework, books on wild flowers, books on the warring Celts who came before us, and even the entire collection of O. Henry short stories, and of course your copy of Pride and Prejudice.

On my writing desk, in a favored spot, lies your old Waltham wrist watch, still ticking. I can’t part with it, because you used to wear it, and now it is precious to me. I have your three lipsticks, even your funny, flowered purse. I cannot part with them, either.

They were yours, once.

I have the various Rosaries you collected, your fine, old black wallet, all your Holy cards, your reading glasses, your sunglasses, your pink and purple satin sleeping mask with the delicate flowers on it. I remember how happy you were when I gave it to you. “I’ll use this!” you promised, “in the daytime if I need to nap.” I wanted you to feel special, and so I bought it for you.

If I don’t look after your things, who will?

I even have your “favorite book,” a small worn paperback about an otter.

Of all things, how could that be your favorite? But it was. You told me so, as we moved you out of your last home, and you gave away all your possessions, other than those few things you insisted on taking with you, those things I am going through now.

I sat across from you, as you pointed to the heavy bound books you wanted me to have, those books on embroidery and needlework, and art, and photography, and I asked you to inscribe them in your beautiful cursive. And you did, reluctantly, amused at my sentimentality. “Oh Theresa!” you said, smiling and laughing as I laid each book on your lap and handed you the writing pen.

And among them that obscure book about a little otter, off to the side.

The Otter’s Tale, by Gavin Maxwell.

“That’s my favorite book,” you said quietly. And I marveled in silence that I’d never known. How could your favorite book be a sentimental 1962 story about an otter?

Then there was the 1965 book that followed, The Rocks Remain, also by Gavin Maxwell. “Would you like this one, too?” you asked. How could I say no? Together with those two books, a 1972 book about whales, by Farley Mowat - A Whale for the Killing. You handed all three of them to me, and I folded them into my bag and took them with me.

I took them, because you wanted me to...

But how is it I never knew you loved the sea and its creatures as much as you did? I thought that was always Daddy’s domain - his love of the sea and the Mermaids, the Silkies and the ancient myths.

Then there was your name, Doris, a name you despised, but a name that always seemed to suit you. A name which I felt had much of elegance and stoicism in it. But you would always shake your head, no, when I told you that. “No one should name their daughter Doris. It is not a suitable girl's name.”

I’ve learned your name means Mother of the Sea Nymphs, or in some definitions, Of the Sea. That your name means Mother of… does not surprise me because that is how I will remember you. You were our mother, and you were an Earth Mother. You would feed the neighborhood children if they were hungry. You would mend their torn clothes, you would feed them cut squares of cheddar cheese and smile as you watched them eat.

It is for all these reasons that you will be remembered.

I remember our conversation of perhaps a month ago, maybe six weeks. You told me: “Tweety Bird, when I finally die, I do NOT want you to be sad. I want you to be HAPPY for me. It will mean this long struggle is over and I will be at peace. Can you do that for me?”

I told you I would try.

On that last night, Amelia sat with you, and prayed for you, and wept for you, and perhaps there was an Angelic congregation that filled that room with its benevolent presence and its peachy light. I genuinely hope there was. For when it was clear you had fallen into your last sleep, and my daughter knew you were at peace, she left you to the Angels and the saints. Less than an hour later, you flew.

You flew and were gone.

How does the new expression go? “Once you become a parent, you become the ghost of your children’s future.”

How true that is, though with you, you will be a benevolent memory, a recollection of the good things you did and tried to do. I will try not to be sad, Mom. I will try to honor your wishes, and think of you as only happy in your new state of being. I will try to forget your last words, murmured, barely comprehensible: “Oh my God. Oh my God. Oh my God.”

Instead, I will remember how two years ago, I made the awkward decision of saying: “I love you, Mom!” at the end of each telephone conversation. How at first, I was afraid to say it, and how you seemed surprised and maybe even embarrassed, too. But then over time, as I said it again and again, it became natural and your voice would smile at me as you said in return: “I love you too, baby.”

The last time we talked on the phone, perhaps three weeks ago, I said it then too. The last thing I said to you, then, and in that hospital room was: “I love you Mom!”

And I do. I love you, Mom.

I love you, Mom.

~Theresa Griffin Kennedy

~Tweety Bird

I am so sorry, Theresa.

What a special daughter you are: “If I don’t look after your things, who will?”

You’re the kind of archivist, Theresa, who holds a family together.

I am sorry for your loss, Ms Kennedy.

We held the memorial service for my father yesterday. I gave the Eulogy, because I was the closest - I am the one (of three sons) who took care of my Dad the last 20 years of his life. My younger brother was perhaps the most “removed” from my Dad. But last November at the VA while my Dad’s body was shutting down and I was unsuccessfully attempting to talk with him to make sure that he was ready to go and okay with the ghouls moving him to “comfort care” mode - I texted my younger brother and told him if he wanted to say goodbye to Dad, he’d better do it NOW. He called a few minutes later and after struggling trying to say goodbye, he said “I love you Dad” - and almost like he came back from the dead (if only for a moment), my Dad somehow mustered “I love you too, Son.” Those were the last words he ever spoke. Like something out of a movie. I told my younger brother a few days ago, “brother, if you ever doubted the depth of love from your father” - rewatch “that” movie.

My advice to Tweety Bird is to embrace your mother’s wishes - the freedom she spoke about - and let her words, “I love you too, baby” ring in your ears like an anthem.