(PORTLAND, OR) - June 23, 2024.

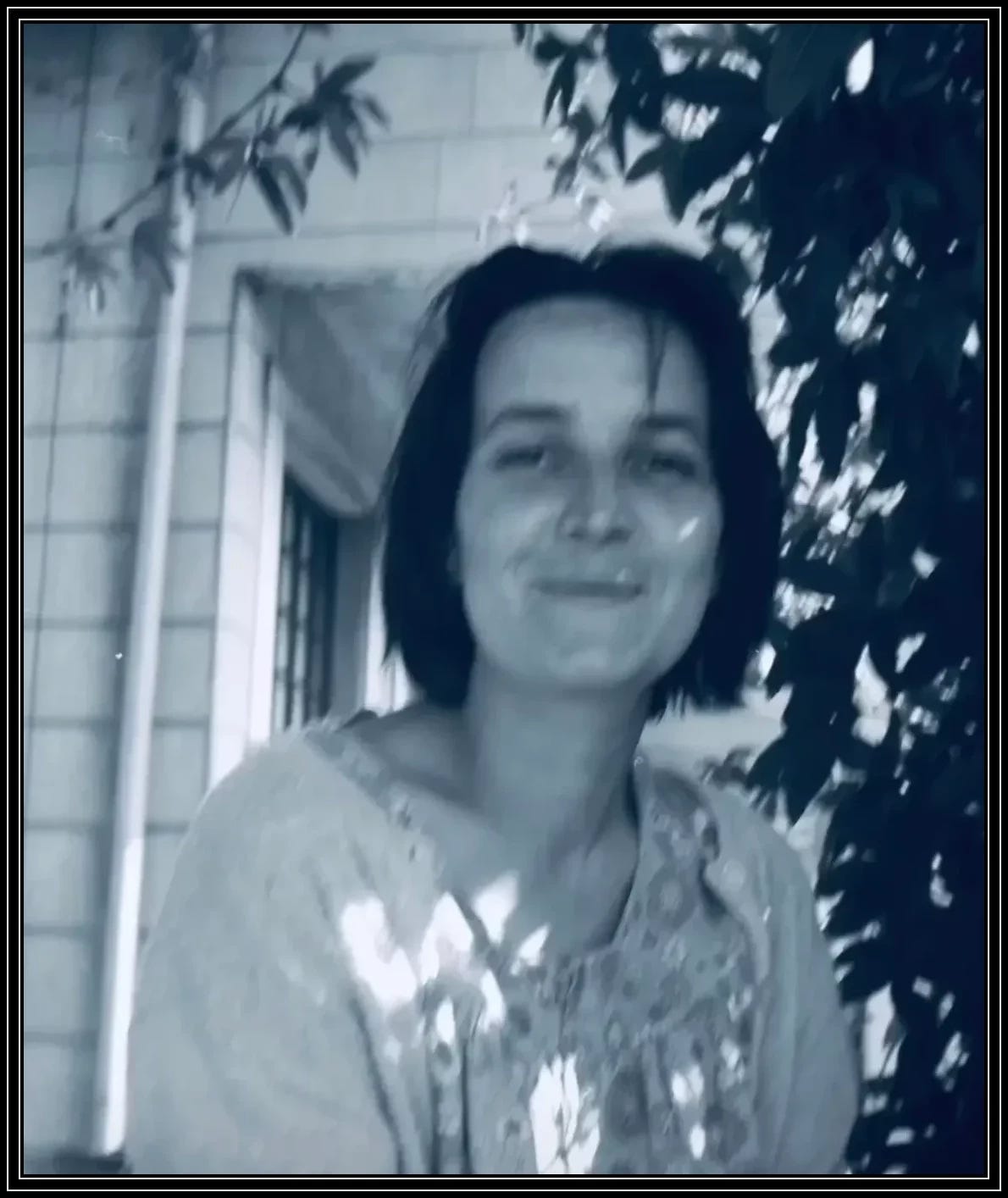

Three months ago today, my mother died.

Yesterday, I collected the last of her things. It was a sad day, collecting all that remains of my mother.

My younger sister had picked everything up from storage, a melancholy collection of 16 tattered boxes. We met halfway - somewhere in SE Portland, chatted briefly and then I set about loading Mama’s boxes into the back of the Jeep. They were things she wanted to keep, for the apartment she dreamed about getting, thinking at the time the boxes were packed, that getting an apartment was a feasible goal for her future.

Of course that would never happen.

Looking at the boxes, stuffed with letters, cards, and other sentimental objects, nothing was organized. It was all just thrown together. As I crammed in the last box, I gazed at the mess of boxes, with spilling contents. It became emblematic of my mother’s often frenetic life and her chaotic and upsetting death - that should have been better - that could have been better. That I still think about and wish had been different.

Mama could never organize anything, looking at her boxes was the last confirmation of something I had known my entire life.

Though she was not a “collector” in the way we think of a collector today, she had too much clutter in the apartment where she spent the last 15 years of her life. It was nothing out of the ordinary, just stacks of letters, small bits of paper here and there, with notes or phone numbers written on them, and knick-knacks, which contributed to an atmosphere of confusion.

A month before my mother died, she asked her doctors to approve having her taken into Hospice care. She knew her time was close. The powers that be said, no. She did not have a “chronic illness” and so their hands were tied. They could do nothing they said. And that is what they did - nothing.

If I had known this, I would have advocated for her, but she rarely asked me to do that anymore. I was too forceful on the telephone and didn’t have the polish of my older sister and older brother, who knew how to talk to doctors and nurses. I was hard on people. If I thought caregivers or doctors were neglecting my mother, I made threats, and was mean. It was what I thought I needed to do, how I thought I needed to be, in order to protect her. But it embarrassed her and in time, she stopped confiding in me about her health issues.

After being denied Hospice care, several weeks later, on March 22nd, suddenly my mother became ill with an acute infection and pneumonia. She was taken to the St. Vincent hospital and the doctors and nurses tried to keep her alive. When I got word, I rushed over. I called my daughter and she rushed over and we met my older sister, who was already there.

Something told me this might be it and that I needed to be there. But I wasn’t sure. Mama had had so many close calls before and had always pulled through. But I knew recently she had been despondent and kept talking about how she was looking forward to death. Her life had been long and exhausting and she was ready, she said. Six weeks before she died, while talking on the telephone, she warned me not to be sad. She knew how I was and perhaps feared that of all her children, I would be the most impacted by her death. She became quietly serious when she said:

“I want you to promise me that when I die, you will not be sad, okay Theresa? I want you to be happy for me, because it will mean this long struggle will finally be over.”

I told her I would try and we laughed, moving on to talk about other things.

On March 22nd, when I got to the hospital, she was not coherent and when she did open her eyes, they fluttered only briefly and she would murmur: “Oh my God. Oh my God. Oh my God,” and nothing else. When I spoke to her she could not respond, but it seemed to me she was listening during her more quiet moments. It was clear she was in pain and when she was in pain, she would fret and moan. At one point, I approached one of the nurses and asked her to please give my mother more pain medication. She said it was not time yet, but in a few minutes she would. Not time?

I stood there feeling useless, and thought of the 1983 film Terms of Endearment, with Shirley MacLaine and Debra Winger. I thought of the scene where the mother screams at the nurses to give her dying daughter more pain medication. Would I have to do that? Would I have to make a scene and demand pain medication for my mother? I stood nearby and approached another nurse. “She’s in pain. She needs more pain medication.” My voice sounded weak and bewildered, like I was pleading. I didn’t want to create a scene, I just wanted them to help my mother not feel anymore pain.

That nurse agreed and came in and worked her magic, near my mother’s IV drip and Mama was given pain medication. It seemed to calm her and I sat down with my daughter nearby. My daughter suggested we pray a Rosary over my mother. I told her that was a great idea and that I knew Mama would want that, as a devout Catholic who had always been extremely religious her entire life. My daughter stood while I sat in a chair, near my mother and we prayed the Rosary, which took almost an hour. It seemed to calm Mama and she became more quiet. Again, I felt like she was listening.

When we finished the Rosary, my daughter became upset. She was bewildered. This was her grandmother. Her feisty, often combative and high spirited grandmother and she had never seen her so ill and out of it. I sat in the chair, not knowing what to do. If I walked across the room and tried to comfort her, would she let me, or would she shrug me off? I didn’t know and I was so tired. So, I sat in the chair and looked over at her. “I’m sorry, honey. Are you okay?” She nodded, but of course she was not okay. She was scared and sad and uncertain.

I turned to my mother. I didn’t know what to do other then try to comfort her. I sat next to her and talked gently, I told her everything would be okay and gently stroked her silky forehead. I couldn’t hold either of her hands because both the backs of her hands were inflamed, covered in huge sores, which I found out later, came from the cat that lived with her in the assisted living home where she was staying. Her hands were extremely painful and even the slightest touch would make her recoil.

I had been out to visit her only 3 months before and her hands had looked fine. How could they have gotten so bad in such a short amount of time?

This was a cat I had arranged to have neutered, paying for part of the cost, a male Siamese named Lucky. He was a friendly cat but kept biting her, which was his way of telling her he wanted more of the treats she would give him, little cat treats that he liked. Yet I’d never seen her hands so torn up before. They were swollen and covered in scabs, a horrible infection on the surface of both hands, discolored black and blue. I tried not be be angry. But how could it have happened? Who was taking care of her? Why had her hands suddenly gotten so bad?

Then my older sister told me the doctors said our mother had an acute bladder infection and that the bites on her hands had contributed to a massive infection. They were pumping her full of several kinds of antibiotics, which I knew would torque her kidneys and lead to kidney failure.

When my daughter left to go and buy food for both of us, after we had been in the hospital room for several hours, I was able to spend time alone with my mother. I sat next to her and stroked her forehead. I whispered words of comfort. I told her I loved her and that all her other children loved her, too. I named them one by one, even the two dead sisters, Margaret and Mary. I told her how much she meant to me and that if she was dying, not to be afraid. I told her she would go to heaven and to “walk towards the light.” I said things that even to me seemed stupid, but I wanted so desperately to comfort her, to make her feel safe. “It’s okay Mom, don’t be afraid. You’re going to go to Heaven now, where you’ll see Daddy, and Margaret, Rudy, Sandy, and Mary.” As I said the words her eyes were shut but it seemed so much like she was listening.

My mind shuttled between wondering if she was dying, and thinking she might pull through. I wished my older brother was there, as an RN he would know everything that was happening. He would know if she was dying and he would tell me. He would be honest and let me know what was happening, but he was sick in bed with a cold and couldn’t come.

I walked up to a tall nurse and asked her: “Do you think my mother is dying?” My voice sounded childlike, the voice of a little girl, as I struggled not to break down. She looked at me in a doubtful, side-eye way that told me she would lie to me and then said: “Well, she seems to be doing fine. She’s stable.” What? Even I knew that was not true. I knew I would never get the truth from any of them. They would all lie to me rather than be honest. It made me hate them. Because I knew they would not tell me what was really happening, as my brother would have done.

After the nurse left and I was alone in the room with my mother, I sat next to her and looked at her sleeping face. I saw the red birthmark on her right temple and remembered how as a small child, I thought all mothers had the same red birthmark. I had asked her about it one day, when I was four, and she had laughed so merrily. “It’s so pretty!” I told her. “Oh, Theresa, you’re such a funny girl,” she had said, smiling down at me as she washed the dinner dishes in the sink.

I had loved my mother’s red mole, the size of a tiny green pea. To me it had always been the most perfect “beauty mark” as she called it. No other mother had a red mole on their temple the way my mother did. It contrasted against her olive skin and beautiful forest green eyes, which she said were hazel colored, but I knew to be deep green, instead. We jokingly argued about it. I’d say her eyes were “forest green” and she would say they were hazel. Just as we argued about her pretty hair. I would tell her it was black, and she would laugh and say it was “dark brown.”

After I’d been in the hospital room several hours the sinking feeling came that she was indeed dying. I knew it but couldn’t seem to face it. I could tell by the way her breathing was unstable. Deep breaths followed by halting shallow breaths. I felt she was dying but what if I was wrong? Again I wished my older brother was there.

When the doctors came into the room and started pulling out a long tube, in a plastic wrapper, from one of the storage lockers, I became alarmed, knowing immediately what it would be used for. “What is that?!” I asked aggressively. “Well, we…we’re going to intubate your mother…” the doctor said tentatively. “No. You’re NOT going to intubate my mother! Didn’t you look at the chart? She doesn’t want any life saving procedures. She’s 88 1/2! That’s almost 90! She has told us all that she wants to go. Didn’t you look at her chart?!”

“I’m so sorry,” the doctor said, “I just came on shift, and… I didn’t look at it. I’m sorry.”

When I said my mother had arranged an Advance Directive, they told me she had not and there was no record of an Advance Directive in their records. I was stunned, but strangely also not surprised. She had told me it was something she was going to do. It was another example of how my mother could not seem to prepare or organize anything. I repeated that she had made it clear, to her children, including me that she did not want any life saving measures taken. I was adamant.

I was also furious. My mother was still semi-conscious through all this. At one point, (before the doctor brought out the intubation tube) they decided they needed to move her body, “to prevent bed sores” a ludicrous thing to do for someone who was so acutely ill. My mother woke up as they began to move her and for a brief moment she cried out in pain. Her eyes fluttered open and she murmured the only thing she seemed able to say: “Oh my God. Oh my God. Oh my God.”

The heartbreaking sounds of my mother being in pain was like fingernails on a chalkboard. I felt my heart racing and wanted to scream at them to leave her the fuck alone! Instead I had to watch in horror as they lifted the sheet and re-positioned her fragile body farther onto the other side of the bed. And for what? Just to torment her?

So, when I saw that horrible long tube, knowing they would want to push it down my mother’s throat, I became sick with anger. I was so glad I was there to advocate for her - to tell them, “No. You’re NOT going to intubate my mother!” My poor old mother would not suffer anymore if I could help it!

When they left the room, I knew I had to use the time left to comfort my mother and comfort myself, too. So, I quietly sang her the lullaby she used to sing to me. I told her how much I had always loved it and reminded her of the times she would sit in the old silver rocking chair in the early 1970s while holding me, my younger sister and our younger brother and sing it to us. My brother was just a baby then and her arms were so full, she could barely hold us all. She would laugh during those happy times, so full of joy to be holding all three of her youngest children.

My younger sister Bronnie had a favorite lullaby called My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean, about a little girl who travels the world. It is an old Scottish nursery rhyme and was always her favorite. As it would turn out, she was the sister who would grow up and travel the world, live in Ireland for ten years and travel all over the United States, including living in Nantucket Massachusetts.

This was the song she would beg my mother to sing again and again, looking off into the distance and thinking about what it meant. She loved that the name Bonnie was so similar to her own name, Bronnie, short for Brongeane, which is an ancient Welsh name meaning Beautiful White Mountain.

My Bonnie lies over the ocean/My Bonnie Lies over the sea/My Bonnie lies over the ocean/Oh bring back my Bonnie to me/Bring back, bring back, please bring back my Bonnie to me, to me/Bring back, bring back, please bring back my Bonnie to me.

My favorite lullaby was quite different and was called Way up High in the Cherry Tree, and was about a mother robin and her babies living in a cherry tree. That was my favorite, and as it turned out, I would by the sister who would only see four states in my life and would never leave the country.

“Way up high in the cherry tree/look up there and you will see/Mother Robin and babies three/way up high in the Cherry tree.”

My sisters favorite lullaby and mine were strangely prophetic about the kinds of personalities we would have and how we would live our lives. My younger sister was fun, lively and a risk taker. I was timid, introverted and a dreamer, who didn’t like to take risks. Opposite sides of a similar coin.

As I sang the lullaby to my mother, she became more still. It felt so much like she was listening, as I continued to stroke her forehead. My mother died several hours later, in the early morning of March 23rd, around 2:30 am, shortly after my daughter had to leave. I had left about four hours before that, thinking that maybe she would pull through. My daughter later explained to me that she noticed each time she came into the room, my mother’s respiration would go up slightly, and that when she left the room, her respiration would go down. She was exhausted too and had been there almost ten hours. She felt if she left, my mother would be able to get some rest and would maybe pull through, just as I was hoping.

About four hours before my mother died, before my daughter left, the doctors gave her some anti-anxiety medication and she finally stopped the mild fretting that would come and go. Her mind was able to turn off and she could let go. She could finally relax.

****

When remembering my beautiful mother, I am reminded again how she could never plan, prepare or organize. She would put things off until another day. In the early days, she was too busy with the bewildering task of mothering nine children, later working full time and always grasping desperately at that fragile cloud of hope that she spent her life chasing. In her later days, she was too busy running from the sorrowful shadows of her past, her Dickensian past of abandonment and being what amounted to basically an orphan. It was a past she never spoke of, a past that I knew haunted her, but that she kept to herself. She used “right brain programming” to help her forget, to help her focus on the positive so her mind wouldn’t go to that “dark place.”

From the time I was four until I turned twelve, I cannot count how many times, I would ask her: “Mom? What are you thinking?” Anytime she was sitting, just resting, usually when we were alone, after dinner, or when the TV had been turned off, her eyes would be a million miles away and I wanted to know. What was it she was seeing? Where was she? And so always the question… “Mom? What are you thinking?’ but she would never tell me. She would just smile and laugh, “Oh, Tweetie Bird, you ask the funniest questions.” And still I didn’t know, but I wanted to know.

I remember when I was little, my mother was always singing while she cooked, dancing around the kitchen, happy to be in the hustle and bustle of our chaotic life, in an old grey house which was barely hanging onto itself and which is now worth over half a million dollars. “I always wanted a BIG family!” she told me more than once, with a happy smile. To make up for the loneliness, I knew, of her ‘only child’ upbringing with no siblings, few cousins, and virtually no family ties.

Her children loved her happy moods and the first thing we asked each other when we got home from school, particularly my sisters and me, was, “where’s Mama?” and then always, “Is she in a good mood?” We helped each other gauge the weather of her emotions by her mood and we would bend accordingly to allow the storm or the fair weather to pass, whichever it happened to be that day. Asking if she was “in a good mood” was the reality of the aftermath of our parent’s 1972 divorce. It took her a good two or three years to get over the anger she felt.

But during her life she could never organize. I watched her start one project after another and not finish them. It caused me sadness to see how she could never follow through. There was my little rust colored chair she promised she would repair and paint. But it never happened and then then the years piled up and I was no longer five and it didn’t matter anymore. I know now, it would have required perhaps an hour to repair and paint, but it was always too much. Life was too chaotic, the demands placed on her too endless. But I never blamed her. I tried to understand, instead.

When she started falling, about twelve years ago, I begged her, as did the rest of my siblings, to please, PLEASE use the cane, and then later the walker, but she refused. “I was only trying to reach for something and before I knew it I was on the floor.” Over ten years of repeated falls resulted in her losing her independence and then her apartment. My older sister pled with her to go through her possessions but she kept putting that off, too. Then when she could no longer walk, or care for herself, she was moved to an assisted living home.

More than once, I offered to have her live with me and I would take care of her, but she said no. My house was too small she explained. She thanked me, but said it would be better to find a small adult care group home.

Before she left her longtime apartment, she and my older sister had hastily packed up 16 boxes with my mother’s most precious things. Those boxes sit now in my living room, as I slowly pick through them. Mostly, there are books, some of them nice books - including a 1939 copy of “Sunsets complete Garden Book,” and a 2019 book of her favorite BBC television program, called, “Downton Abbey: The Official Film Companion,” by Emma Marriott.

Then there were a few old paperbacks with the covers pulled off. Few people will know what that means, but I do. When my mother was the manager of the Book Department at Frederick & Nelson, in the 1970s and 1980s, the store would discard old books that didn’t sell well. Rather than donate them to a charity, or the library, which would have been the smart thing to do, they would instruct the workers to dump them, throwing them in the trash. Eventually, the books found their way into a dumpster. To fend off dumpster divers, who might find the books, and read them or sell them, Frederick & Nelson instructed the Book Department workers to RIP off the front covers.

It was 1979 when I first learned of this wasteful, selfish rule. A stack of paperbacks sat on the counter near the cash register and my mother was methodically engaged in pulling off the covers. She was philosophical about it. While I was furious and told her with my usual 13-year-old passion that it was wasteful and an outrage, she laughed, suggesting that I take some home with me. I would have none of it. They were “ruined” I said. Why would I take home a paperback book missing its cover?! But she did take them home. She was a realist. It was still a book, and so what if it was missing its cover? It could still be read. You could still benefit from reading the book.

So there they sat, in the dusty box. Paperback books missing their covers and I knew they were useless, and that I would have to throw them away. I couldn’t possibly keep them, but throwing them away seemed like a slight towards my mother. I felt conflicted as I looked at the jumbled mess of all those silly ancient paperbacks with their missing covers.

I have found other things of interest. Old letters from before Mama married my father, from 1953, when she was still Miss Doris MacDougall. Such a fine name, I always thought. But she hated her first name, telling me more than a few times: “Doris is NOT a suitable name for a young girl.” I asked why she didn’t use a nickname, like Dorrie, or Dora? But she scoffed and insisted that Doris was the worst name imaginable and even a nickname couldn't redeem it.

When I decided I would keep my mother’s purse and all its contents, I found among her ID, and lipsticks, the original Social Security card she had gotten when she was still an unmarried teenager, having graduated from high school and was living alone in a “one room efficiency” while working at a department store full time, at slave wages. I looked at the little card and realized it was at least 70-years-old and she had kept this in her various purses her entire life, but I’d never known. I felt sad looking at at the little, perfectly preserved scrap of government paper. There was a modern social security card also in her purse but she had kept the old one, the original one from when she was a young woman just starting out in the world, full of hopes and dreams for a better life. Why? Why had she held onto it, to go with her through all her travels, for decades?

Looking at her original social security card made me feel so sad I came close to crying but didn’t. I just swallowed the sadness and reorganized her purse, taking out the contents, brushing them off and shaking out the dust and lint from the bottom of her funny little purse, with the large flowers and the bright primary colors.

I sit and look at the boxes of these dusty, for the most part valueless objects and lament my mother’s difficult life, and the ghosts from her horrible, Dickensian childhood and struggle to let them go. They are only objects but they contain in their makeup, her fingermarks, her hands once held them, her voice once vibrated above them, they were valuable to her. I struggle to let them go. But I must. I must sort through them, keep the personal letters and photos that are important, and say goodbye to the rest. To the old yellowed paperbacks, missing their covers, to the knick-knacks that are falling apart, and the other mysterious minutia that she wanted to keep, for the “new apartment” that would never happen.

It has only been three months since she left, glad to fly away and be free of his heavy, sad world, but I still grieve her absence.

I grieve not being able to talk with her, or listen to her lecture me about God and religion and the importance of praying. I grieve not being able to hear her voice when she would tell a good story, and my mother was such a great storyteller. And despite her denials, she loved to gossip, I miss that, too. I miss her good, simple moral awareness and her sometimes inexplicable self-sabotaging behavior, when the ever present mental illness showed itself and I wondered about how her mysterious mind worked, always reminding myself that she had suffered in ways I would never know, in that Dickensian childhood of hers going all the way back to dismal Seattle, in the 1930s.

I miss knowing that she loved me and would worry about me if she thought I was sick, or not doing well. I miss talking about books with her and what book she was currently reading, and why it was good, or what book I was reading and why I liked it. I miss her occasional drama and the way she would get angry about current events and social injustice and her often comical biting sarcasm.

I miss how she knew all the womanly arts, like sewing, knitting, crocheting, embroidery and quilting. I could always ask her for advice, regarding those things, particularly patchwork quilting, which she basically showed me how to do. I still miss her knowledge of roses, lilacs, food, nutrition and cooking. I still miss her.

I still miss Mama.

~Theresa Griffin Kennedy

To read an elegy poem, look down below…

Elegy for Mrs. Doris Anna Griffin…

Elegy for Mrs. Doris Anna Macdougall - Griffin - a Personal Lament

September 7, 1935 - March 23, 2024

It has been seven days since you flew.

Seven days since my daughter and I sat with you, prayed the Rosary, The Sorrowful Mysteries, over your sleeping body, the last of your clan to be with you. Seven days since we told you we loved you, and that you were Heaven bound. Seven days since you died on a Saturday, the same day you were born, the day of The Joyful Mysteries.

Seven days since I stroked your silky forehead over and over with my left hand, gently, awkwardly, telling you in whispers: “It’s okay, Mom. I’m here. Theresa is here. I’m here now. I’m here with Amelia.” Seven days since I watched your brow and face relax, seven days since I promised you I would see you again, knowing that at least in this world, I would not.

Seven days since my daughter wept over you, and prayed over you and ached over you, the last to be with you, the last to touch you, kiss you and comfort you.

Mama, how do I tell anything of your long story of hardship and suffering? How do I begin that story? How do I end it? How you bore nine children? How your endless optimism informed my own optimism? How your bottomless sadness informed my own bottomless sadness? How religion was the only thing that sustained you, the only thread of hope you had in that lonely year, 1939, the year your grandfather told you that God would always love you and you would never be alone?

It was the year of great films, at age four, that they took you away from your mother and rescued you from the blue din of her madness. How do I tell of that Oliver Twist childhood? Is it even possible?

Probably not.

I have gathered your things, just the other day, four white bankers boxes filled with small objects of little value. Four of your fine blankets, and a few of your favorite articles of clothing. They hang in my closet now. Your favorite jackets, including the silk one that made you feel so special.

I am looking for clues, in much the same way I looked for clues when I sorted through Mary’s little trinkets, after she died. She, the third of your five daughters and the second daughter to die before you.

Pretty things that sparkled and shone. Pretty things still in their packaging, for that was how Mary kept her precious things, precious, by never unwrapping them, by keeping them pristine, and untouched.

I am sorting through your old things now, looking for clues, the way I’m always looking for clues.

Daddy said once: “You're the archivist of this family, Theresa.” It made him smile to see the things I had saved from the city dump moldering across town. Old wooden toys he had made when we were kids, all of the letters and cards he ever sent me, old photographs, odd things of little value, like the wooden display that you decorated every Christmas with the Nativity set we used to have.

These silly, sentimental things are alive with our memories, a glowing collection in dust and purple shadow.

And I have the books you loved, books on embroidery and needlework, books on wild flowers, books on the warring Celts who came before us, and even the entire collection of O. Henry short stories, and of course your copy of Pride and Prejudice.

On my writing desk, in a favored spot, lies your old Waltham wrist watch, still ticking. I can’t part with it, because you used to wear it, and now it is precious to me. I have your three lipsticks, even your funny, flowered purse. I cannot part with them, either.

They were yours, once.

I have the various Rosaries you collected, your fine, old black wallet, all your Holy cards, your reading glasses, your sunglasses, your pink and purple satin sleeping mask with the delicate flowers on it. I remember how happy you were when I gave it to you. “I’ll use this!” you promised, “in the daytime if I need to nap.” I wanted you to feel special, and so I bought it for you.

If I don’t look after your things, who will?

I even have your “favorite book,” a small worn paperback about an otter.

Of all things, how could that be your favorite? But it was. You told me so, as we moved you out of your last home, and you gave away all your possessions, other than those few things you insisted on taking with you, those things I am going through now.

I sat across from you, as you pointed to the heavy bound books you wanted me to have, those books on embroidery and needlework, and art, and photography, and I asked you to inscribe them in your beautiful cursive. And you did, reluctantly, amused at my sentimentality. “Oh Theresa!” you said, smiling and laughing as I laid each book on your lap and handed you the writing pen.

And among them that obscure book about a little otter, off to the side.

The Otter’s Tale, by Gavin Maxwell.

“That’s my favorite book,” you said quietly. And I marveled in silence that I’d never known. How could your favorite book be a sentimental 1962 story about an otter?

Then there was the 1965 book that followed, The Rocks Remain, also by Gavin Maxwell. “Would you like this one, too?” you asked. How could I say no? Together with those two books, a 1972 book about whales, by Farley Mowat - A Whale for the Killing. You handed all three of them to me, and I folded them into my bag and took them with me.

I took them, because you wanted me to...

But how is it I never knew you loved the sea and its creatures as much as you did? I thought that was always Daddy’s domain - his love of the sea and the Mermaids, the Silkies and the ancient myths.

Then there was your name, Doris, a name you despised, but a name that always seemed to suit you. A name which I felt had much of elegance and stoicism in it. But you would always shake your head, no, when I told you that. “No one should name their daughter Doris. It is not a suitable girl's name.”

I’ve learned your name means Mother of the Sea Nymphs, or in some definitions, Of the Sea. That your name means Mother of… does not surprise me because that is how I will remember you. You were our mother, and you were an Earth Mother. You would feed the neighborhood children if they were hungry. You would mend their torn clothes, you would feed them cut squares of cheddar cheese and smile as you watched them eat.

It is for all these reasons that you will be remembered.

I remember our conversation of perhaps a month ago, maybe six weeks. You told me: “Tweety Bird, when I finally die, I do NOT want you to be sad. I want you to be HAPPY for me. It will mean this long struggle is over and I will be at peace. Can you do that for me?”

I told you I would try.

On that last night, Amelia sat with you, and prayed for you, and wept for you, and perhaps there was an Angelic congregation that filled that room with its benevolent presence and its peachy light. I genuinely hope there was. For when it was clear you had fallen into your last sleep, and my daughter knew you were at peace, she left you to the Angels and the saints. Less than an hour later, you flew.

You flew and were gone.

How does the new expression go? “Once you become a parent, you become the ghost of your children’s future.”

How true that is, though with you, you will be a benevolent memory, a recollection of the good things you did and tried to do. I will try not to be sad, Mom. I will try to honor your wishes, and think of you as only happy in your new state of being. I will try to forget your last words, murmured, barely comprehensible: “Oh my God. Oh my God. Oh my God.”

Instead, I will remember how two years ago, I made the awkward decision of saying: “I love you, Mom!” at the end of each telephone conversation. How at first, I was afraid to say it, and how you seemed surprised and maybe even embarrassed, too. But then over time, as I said it again and again, it became natural and your voice would smile at me as you said in return: “I love you too, baby.”

The last time we talked on the phone, perhaps three weeks ago, I said it then too. The last thing I said to you, then, and in that hospital room was: “I love you Mom!”

And I do. I love you, Mom.

I love you, Mom.

~Tweety Bird

~Theresa Griffin Kennedy

Share this post